Critical Theory & Critical Theories

Introduction

This is the fourth part in our series on Jesus and Academic Culture. The first three parts of this series were primarily aimed at helping evangelical Christian professors better relate with their non-Christian colleagues. We tried to do so by highlighting the importance your political opinions play in the hearing of the gospel by others—especially if you do not share the same cultural or political standpoints they do. There is a tendency in your audience to make a fairly large number of assumptions about other kinds of beliefs you have and the kind of person you are, if you are identified as an evangelical. (Note hyperlinks below are in burgundy.) You can review, and we think it is valuable to review what was said in those three previous articles, for context: Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3.

(Read our ministry’s political advocacy policy, here. We believe that what we share in this article is not in violation of that policy. What you won’t get from this is, who to vote for in the next election or which political party to belong to.)

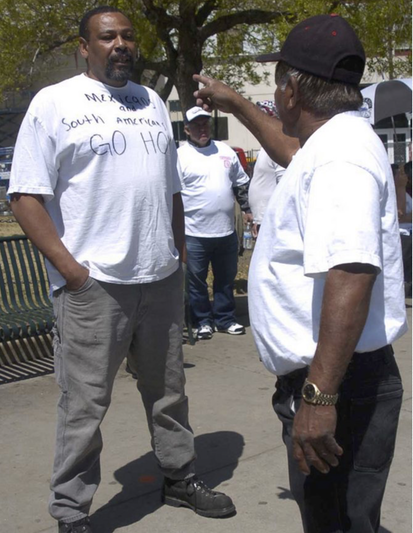

Mexican Recognition Day

Denver, Colorado

2004

Photo Credit: Gary Rhodes

In order to increase the progress of the gospel, it was earlier argued that we need to better understand the phenomenon of secularization and the phenomenon of pluralism that has occurred and what that means to gospel-related conversations with our colleagues.

We also argued one finds a counter-intuitive, pragmatic intellectual approach to knowledge more broadly than expected in academe, and we recently focused on how it plays a role in emphasizing the importance of changing cultural institutions (especially the political aspects).

This pragmatic approach is very different from the widely shared opinion of academic mood, which suggests that by our research and conversations, we are seeking the truth that is out there to be discovered. It is too easy for all of us to believe that the goal for everyone is truth, yet for many it is not. We often find ourselves talking past each other in this culture when we fail to heed this nuance, and we don’t want to make that audience analysis mistake.

Our third installment, which you can view here, was aimed at discussing how our political affiliations influence our interactions with even our fellow Christian professors, and offered some suggestions on how to begin to heal some of the self-inflicted wounds within that discussion.

*************

In this fourth article, we circle back for a deeper analysis into a particular set of relevant political ideas that flourish in academe, which have had a great deal of influence on both the culture we seek to reach and the intramural debate we earlier identified among ourselves. We have certainly talked about this before, but here we will take a deeper dive.

Our aim here is analytical in nature more than it is aimed at giving you applications in your practice of evangelism in light of this analysis. Certainly, what we say here can be profitably applied to evangelism with your colleagues, but the ideas we will cover merit some explaining. It’s good to make sure we understand these ideas, as they shape our academic culture in powerful ways. After our analysis, we can always ask if these ideas and their ends—good and bad—justify the means by which they are carried out.

What we will do is examine some of the roots and shoots of Critical Theory, which include critical race and gender theories, identity politics, intersectionality, and other related aspects of the prevailing academic climate. We will define these terms along the way and hopefully avoid 1) the genetic fallacy of simply dismissing them because of their questionable historical pedigree, or 2) ignoring their present merits and demerits. We hope to get beyond merely a lambast of historical secular Marxist ideology, from which these ideas (or ideologies) apparently find their roots.

We also want to acknowledge that this area of research is as wide as it is deep and we cannot hope to cover all the bases in this article. Nonetheless, we aim to make things simpler without being simplistic in our approach. Critical Theory and its critical theories are ubiquitous in our present culture and yet we have been surprised that many we speak with—even within academia—only know it by whatever terms the current propaganda spotlight shines on, and thus many never get a sense of its whole picture.

Our Intentions & Motivation

What we intend to do in this article is 1) provide a framework for understanding what the leaders of this ideological movement say and apparently mean; 2) ask questions of it, including a most basic question, if Critical Theory and critical theories are a mechanism for identifying the need for and a means for social change, is it Christian and would Christ endorse such a theory and/or its shoots? This can present a challenge because as we shall see, Critical Theory calls into question the lens by which we understand what Christianity is; and 3), finally, what should serious and thoughtful Christians do about all of this?

Our motivation for this analysis is to 1) help clarify for Christians in the professorial community what we think Critical Theory and critical theories amount to conceptually, theologically and what they amount to practically; and 2) make sure that Christian professors have enough information about those things to enter into a dialogue about whether a Christian professor should endorse these things as theologically permissible. While there are important implications from this that apply to interactions with our colleagues about the gospel, our main focus is to raise consciousness on this very influential and dynamic cultural tour de force, that seems to be winning the day even as we write.

Defining Some Terms

Let’s begin by defining Critical Theory. According to the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy—a fairly detailed and worthwhile read itself—Critical Theory has both a broad and narrow meaning “in philosophy and in the history of social sciences.” The narrow sense has to do with some German philosophers and social theorists “in the Western Marxist tradition.” (See the Frankfurt School, here and here.)

The broader sense of the term has to do with the many critical theories that have emerged and bear some relationship to its self-defined purpose which was to identify and overcome “the domination of human beings in modern societies.”

Critical Theory claims to seek virtues that involve practical (not just theoretical) concerns, in that it “seeks human emancipation from slavery,” acts as a “liberating” influence, and works “to create a world which satisfied the needs and powers” of human beings (Horkheimer 1972, 246). In other words, it seeks to uncover and transform “all the circumstances that enslave human beings” and, we think, could therefore lay claim to fostering and being related to specific critical theories such as (but not limited to) post-colonial theories, contemporary feminism, and critical race and gender theories.

Critical theorists see their task as morally prescriptive—but practical: human emancipation. They argue that it’s a moral good to emancipate humanity from whatever they deem as enslavement.

In light of these practical goals of identifying

and overcoming all impediments to human freedom, it has self-consciously

restricted itself to empirical “interdisciplinary research that includes

psychological, cultural and social dimensions, as well as institutional forms

of domination.” It seeks the “‘transformation of capitalism into a

‘real democracy,’” in which such moral and practical control could be exercised.

General Framework for Understanding

Critical Theory was first developed in the early 20th century by some German academic intellectuals—the Frankfurt school— and we believe it’s best understood as an evolving, pragmatic form of Marxist political theory, and an evolving normative (moral) ideology that seeks normative practical ends—what it deems “emancipation” and the “liberation” from domination by just about anything in culture that is thought to impede this progress.

In its earliest years, its intellectual leaders worked to frame the movement, motives and methods in terms of the inspiration provided by Marxist “insight” into the economic realm, and expand those kernels into an understanding of all of culture. One could say it was both (ironically) conservative in nature, attempting to conserve what they thought was the best of Marxist theory and reformist in nature—seeking to refine, improve and then expand the influence of those original ideas in every sense, at least from a Marxist and secular perspective.

During the 1930s, this school of thought was persecuted by the rising fascist regime in Germany, and escaped to Columbia University. That diaspora then spread more broadly in higher education within the United States and elsewhere.

Critical Theory is offered as both a tool for analysis of culture and as a mechanism for change—it provides a means for changing culture through activism. It has come to focus on power as it is exercised in a myriad of ways in culture. Through activism (and in its extreme form, by “any means necessary”), they seek to gain power to match and overthrow the oppressors and the systems that sustain them.

It includes an analysis of language and communication structure as a means to gain and retain power within a culture. Its shoots provide analysis of culture that is alleged to provide “social facts,” from which the activists seek change. For example, one such “social fact” in critical race theory is that America’s founding documents (e.g., the Constitution) are best understood as profound expressions of the overt racism of the ruling white class in America.

Critical Theory and its theorists seek to identify and overthrow these unjust and immoral system(s) and replace them with more just social structures where by contrast, the oppressed rule. The various particular critical theories mentioned above are expressions of Critical Theory values and tactics, contextualized for a specific social and structural barrier it seeks to destroy. Thus, it is fair to say that these critical theories are inspired by overall Critical Theory and are a primary means to extend its roots into diverse social niches within the culture.

It follows that Critical Theory and “its” critical theories share large conceptual overlaps in terms of their analysis, goals and methods, but they should not be conflated. Sometimes the “social problem” to be brought down by activism is identified as racism, sometimes it is identified as xenophobia or homophobia. Indeed, the list of the identity groups of victims in need of emancipation can be quite long, and their internal relationships can seem quite subtle to the uninitiated.

By means of their analytic “tools" they divide up culture in terms of the oppressed and oppressors, for instance, like haves and have nots—those who deserve “victim status” and those who are the abusers of the victims. Implicitly it seeks to create “new" winners and “new” losers in the social justice moral landscape, to even up the score and to right the social wrongs it sees; and, nowhere can this phenomenon be observed and tracked more, than in academe. Academe is the de facto intellectual vanguard of the movement and a main target of its transformational aspirations. Follow our recent tracking of some of its causes in academe: here, here and here. Of course, in step with International Marxism, it also keeps its eyes on the larger prize of globalized transformation in its image.

Tactics for change also play an important part of understanding Critical Theory. One of its major activist contributors has been Saul Alinsky, famous for his book, Rules for Radicals: A Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals (Endnote 1). His basic thesis is that radicals (like himself) need to be invited in as a consultant to specific political and social identity groups who consider themselves “enslaved” or oppressed. When brought in, they discuss with those who invited them, what are they upset about and ask what can be done to bring about change. The task of the invited radical is to help the group leaders, by a process of interrogation, find out and clarify what the group wants to change and to clarify what DOES NOT work as a means for change. And, what does Saul Alinsky think does not work? In short, what he says does not work are attempts to achieve reform created by mutual love and mutual understanding. (Endnote 2)

From their point of view, what “works" is using the social group’s activists to agitate to the point of conflict between the “oppressed” and its “oppressors.” They explicitly say they do this in order to gain power, because they believe nothing of substance can be gained without it or without the threat of power. You can get a sense of how Alinsky radicalizes oppressed groups from this YouTube video, where he encounters members of the Rama Indian Reserve. In Alinsky’s words, “The job then is getting the people to move, to act, to participate; in short, to develop and harness the necessary power to effectively conflict with the prevailing patterns and change them. When those prominent in the status quo turn and label you an ‘agitator,’ they are completely correct, for that is in one word, your function - to agitate to the point of conflict."

Initially, Critical Theorists began teaching these kinds of views at the universities and in particular how education and socialization play a major role in either garnering power or holding on to power. These forces, along with economic factors, are what they believe creates the oppressors and the victims. It was typically taught as a dialectic, and the “education” was used as a tool to wake people up to the social issues the movement wanted to identify, critique and change.

Along the way, terms were coined, such as: identity politics—a means to secure political and social freedom for a “specific constituency, marginalized within the larger context of society”; woke—historically associated with critical race theory, where the radicalized are awakened (or woke, as in African-American slang) to social facts and issues that enslave them; intersectionality (as a part of discrimination)—a term that describes how a person can be victimized in a number ways; for instance, a black gay woman has suffered more injustices and therefore has greater credibility to speak than a white, heterosexual man, because of the layers of social injustice she has endured and endures; political correctness—term for the attempt for those sympathetic with critical theories to eliminate or restrain certain political language and social expressions that they deem as offensive or that are considered a means to disadvantage particular identity groups in society. All of this is part and parcel of the two senses of Critical Theory and critical theories we discussed above.

Relevant Questions

If that’s the general drift, Christian scholars can and should ask as to whether such a project of social transformation—really social revolution, taken lock stock and barrel—is appropriately a Christian one? Or can it, with some slight tweaking of its goals, motivations and methods for change, be properly baptized into what can be considered legitimate Christian cultural aspirations? I say baptized, because its roots are certainly secularist—and that fact alone should raise the eyebrows of Christian intellectuals. But again, we say that with some restraint, to side-step a genetic fallacy charge. Nonetheless, its Marxist-Leninist roots in methodology for change, produced by confrontation, conflict and gaining control (power), have influenced its shoots in ways that continue to this day and should be evaluated on the merits.

Maybe we should begin our analysis with the question, is the emancipation of structural and cultural domination of humans—in all its supposed forms—a Christian virtue? If so, why, and if only partially, which ones and if so to what degree? Then we can ask how this emancipatory project has conducted itself, including how Christian streams of the movement have conducted themselves and whether the ends have or will justify their means.

1) Are The Goals of CT Worthy of Being Considered a “Virtuous" Christian Path/Project to Bring About Social Change?

We enter this section with some trepidation, because there are and have been (historically) theological schools of thought about how much, if any, involvement a Christian should have in culture outside the Kingdom of God. This in-house discussion goes back at least as far as Augustine’s The City of God (Endnote 3), but continues in more contemporary times by H. Reinhold Niebuhr’s nouveau classic, Christ and Culture (Endnote 4), and even more recently and in more evangelical terms, D.A. Carson’s erudite Christ and Culture Revisited (Endnote 5).

At the extremes of the spectrum of Christian involvement in culture lie two disparate models. The “separatist" (non-involvement) model and the “transformational" (high involvement) model. We leave to you to read up on these and other typologies of Christian involvement in culture and compare them with a high level theological understanding of scripture. We acknowledge that this is not easily accomplished. We typically form these points of theological perspective from our experiences growing up. As adults, it is still important to understand the range of answers given and their theological justification.

Lacking the space to do that in this article, but not wanting to completely overlook calling these important considerations to your attention, we will make what we think are some theological assessments (hopefully inspired by scripture—we will leave that judgement to you) about Christian involvement in culture.

First, the whole idea of our Creation doctrine, where humans are understood to be made in the image of God and thus having both intrinsic worth and instrumental worth, does have a basis in scripture. The fundamental dignity of humans, even fallen humans, provides a strong theological web of support for the decent treatment of all humans (and humanity as a whole) and in particular instances as well. If such an understanding of dignity represents (and we think it does) God’s nature and will, what sort of systemic political goals and achievements for humans should we seek? Have we not also been taught by the Lord to pray, “Thy will be done on earth as it is in heaven?”

As a first approximation, it certainly seems reasonable to think that Christian theology at a minimum supports the emancipation of some systemic (structural) cultural domination of humans, and does not merely support the eternal salvation of humans, as important as that is. How many of us American Christians appreciate the transformation of culture represented by our revolution from British colonialism? How many of us prefer the model of representative democratic self-government as opposed to a systemic model of despotic rule, allegedly sanctioned by divine right?

However, should we not also ask, why think all things deemed by critical theorists as barriers to human emancipation are actually worthy of the called for deconstruction (and destruction)? Isn’t it prudent to consider this if only to avoid the “some” to “all” fallacy? Are all of the identified deconstruction projects Critical Theory virtuously Christian deconstructions? If not, which ones are and which aren’t, and on what basis?

The point of that is that it is likely when Christians agree with what critical theorists identify as a barrier to experiencing the human dignity they deserve, they will likely agree so on a different basis. And, it is likely that Christians when they do agree with them will think what the critical theorists suggest as remedy for removing the barrier goes too far. For instance, many Christians would agree the LGBTQ community suffers violence at the hands of members of our society and that violence and dehumanization is morally wrong. However, those same Christians might hold biblical views that find a great deal of what that community says about human sexuality are at odds with doctrines they hold as a part of their faith stance. How can Christians juggle the public policy issues in a way to hold both views intact? Wouldn’t it be prudent for Christians to want to find ways to keep both positions for the common good and the glory of God? In a somewhat similar fashion Christians will likely find themselves agreeing about concerns related to oppression, but disagree with many secularists about how that parses out on abortion.

This also raises the question how much violence is tolerable for a Christian to achieve total “emancipation?” The prophet Amos in the Old Testament decried, “For I know how many are your offenses and how great your sins. You oppress the righteous and take bribes and you deprive the poor of justice in the courts.” How far do we go to right these wrongs? Not all ends justify all means. Can we righteously go as far as doing evil that good may come?

Second, how should Christians think about the methodology critical theorists use to identify social injustices--by the alleged means of "carefully constructed" demographic and sociological studies? In this scenario, the “scientific” enterprise and scientific authority would be used to help reveal subtle prejudices and barriers to emancipation that are entrenched in any cultural tradition and in law. Wouldn’t Christ be in favor of serious work to identify those injustices and insults to intrinsic human worth?

However, it also seems wise to wonder if the sociological studies to be constructed and conducted will actually produce an objective result. This is not to suggest that there is a conspiracy to slant the data in academe, but rather to suggest that even people who study these things in good faith can have trouble avoiding confirmation bias. Since a great deal of research has been done under the social justice banner, shouldn’t we take a good look at how that work has faired? This “reality” in research, especially so in the so-called soft-sciences and humanities should encourage Christians in the fields to keep an eye on work being done, including looking for indications of research agendas, lowered standards of scientific proof, and so on.

Is there precedence for this? We think yes. Don’t scholars keep their eyes on major pharmaceutical research because of the big corporations involved, and the potential conflict of interest that could affect the results? If it happens in that domain, why not in this? Of course, such an undertaking must be done with integrity and care—we’re also subject to confirmation bias. Another problem here is the consequences these skeptical concerns will have on the careers of those who get the word out, if improprieties are found, so be very careful! Sometimes questioning their findings has been met with very strong rhetorical resistance; and depending on the case you may be given a label like racist, homophobe, or identified with a host of other possible unflattering tags.

Nonetheless, it is important to say that Christians should not automatically turn a deaf ear to what Critical Theory identifies as injustices. Some of them may be spot on, others might be close to what a Christian could endorse, and with some tweaking and clarification offer qualified and limited support for certain reforms with a good conscience. In so doing it seems important to appropriately distinguish (in the right venues and at the right times) between the secularity Critical Theory brings to the table and what we bring to the table, informed by our Christian faith.

Third, evaluation of Critical Theory should involve analysis of the widely bandied about terms “social justice” and “social injustice,” because they are often used as if they are self-defining. A little investigation can show those terms carry a lot of freight. For example, whose understanding of what constitutes justice do we go with in our “secular” society? Can Christians go with Plato’s or Aristotle’s notion of social justice? Remember, both Plato and Aristotle thought “justice” is served within a society that tolerates slavery on the grounds that some people are by their nature “meant” to rule and others by their nature “meant” to serve as slaves!

"…nature herself intimates that it is just for the better to have more than the worse, the more powerful than the weaker; and in many ways she shows among men as well as among animals , and indeed among whole cities and races that justice consists in the superior ruling over and having more than the inferior." Plato, Gorgias

"For that some should rule and others be ruled is a thing not only necessary, but expedient; from the hour of their birth, some are marked out for subjection, others for rule… [A]nd indeed the use made of slaves and of tame animals is not very different; for both with their bodies minister to the needs of life." Aristotle, Politics

Or do we instead sign up for a Rawlsian (also secularized) conception of those terms (Endnote 6)? His so-called vale of ignorance, allegedly enforced to provide social role fairness, could permit morally unacceptable lifestyles to gain "systemic justification,” because the theory seeks only thin common behavioral denominators as guidelines, without the “taint" of philosophical, moral or religious ideology. What is the logic of this kind of relativistic and pluralistic position, and how far do Christians let this go if they adopt it… to its logical conclusions? Can a moral line in the sand be drawn that stands apart from what we commonly agree upon? If we “permit” egregious immoral behavior, do we become complicit with it?

Fourth, an even more serious question for Christians about Critical Theory can be asked when what amounts to Critical Theory is taught and communicated among Christians as the gospel itself. Arguably this has been done in parts of Latin America, where a Marxist interpretation of the gospel is called “liberation theology.” In our judgement, there was an “over-reliance on Marxist ideology and under-reliance on orthodox theology.” It is easy for those who adopt far left ideology and those who adopt far right ideologies to “see” their truth in the Bible. (See this article entitled "The Biblical Gospel" for a good summary of the orthodox position on what the Biblical Gospel is and how it suggests we work from the centre of our gospel to these other important issues and not vice versa.) Often there is a confusion between the means to a relationship with God, which is God’s grace in Jesus Christ, and the results of faith, which are good works. Without the results of good works, we simply have the wrong kind of faith. However, it is much more complicated knot to entangle to think (and likely mistaken to think) you can simply draw a straight line between the the correction of every instance of so-called social injustice and theological permissibility; and, that’s because not every instance of what is currently claimed as social justice is something that necessarily fits with the gospel of grace.

However, as we said above, this claim about what the gospel “is” can be questioned by adherents of critical theories and by others. That’s because it has been argued that everyone takes their own cultural baggage into their reading of scripture. White Christians bring their “whiteness” into the reading of scripture (and one could add, in their “reading” and creating of culture); but then it could be argued, black Christians bring their “blackness” to the reading of the gospel and culture, and other minorities bring their minority cultural baggage into their reading of the gospel and culture, so that doesn’t seem to get us very far (Endnote 7).

Nonetheless, critical theorists argue that minority culture brings something to cultural critique that the majority culture cannot: they have been oppressed and have “experienced” it in a way that others cannot understand. Accordingly, critical theorists hold that this experience gives them a higher (intellectual) standing in the conversation andthat their experience of oppression can negate a lack of evidence for it or even evidence to the contrary (Endnote 8). However, if true there is something of a contradiction here. On the one hand, many critical theorists want to say their identification of cultural oppression is based on “science,” which presumably includes well done statistical analysis, and on the other they seem to skip the “science” when it comes to the authority of minority experiences. That doesn’t seem to make sense either.

Add on to this (as we will discuss in the next section) the propaganda wars that ensue, and we can see how this can lead to both sides overstating their cases. Maybe that’s why as Christians of all colors we should seek the humility it takes to carefully listen to those who allege their experienced oppression and engage in fruitful dialogue for changes. See Acts 6:1 and following, and see also Philemon. This way of doing things should be especially true for the in-house church discussion of the effects of biases, but also with the appropriate changes, can be adapted to cultural change movements of Christians and for reforms outside the church.

Fifth, despite the cultural conversation and debate about these and other related things in the last 70 years—that should have involved many more evangelicals—proponents of critical theories have not needed to do so; for the most part, they have won the day in the public consciousness and in law. The discussion among the intellectuals is largely over. The activists seek to take that big win to every cultural front and in every sub-cultural backwater that exists.

Their agendas have been largely successful in the curriculum battles, in the extreme feminist agenda—including “reproductive” abortion justice, in the “diversity” for the sake of diversity hiring agenda, in the extreme anti-colonial theory, in the anti-free speech agenda, in “environmental” justice, in the LGBTQ justice agenda, and so on. Some of these social ground “losses" were arguably deserved, but with no unmovable line in principle (other than what flies today), should we not expect that what is taboo today will be a human rights cause célèbre tomorrow? Is this supposed to be okay for us?

2) Critical Theories: Has Their Project Been Conducted in a Way That Exemplifies a “Virtuous" Christian Path/Project to Bring About Social Change?

A great deal of what we discussed above, mutatis mutandis, can be profitably included when one evaluates the individual critical theories. They all seem to see themselves individually as tackling some specific kind of barrier to human rights and dignity in order to help emancipate its victims. What can be said about Critical Theory pro and con, on a theoretical and theological basis, can with the appropriate changes be applied to the “broader” critical theories mentioned.

However, the thing we wish to examine closely in this section is the modus operandi incorporated into activism in these theories. The theory and the praxis come as a whole. How are they in fact supposed to be operated on the ground? That inspection may aid us in our analysis of how compatible the whole Critical Theory and critical theories bundle is with our Christian faith.

The first thing to see (and we talked about this earlier), is that the vehicle for social change recommended by the critical theorists is about getting power to force change. How Christian does that sound? On the other hand, it’s possible and maybe even probable that cultural dissonance is a means to bring important issues to the forefront. The problem is finding the right balance of cultural dissonance that keeps the culture aware of social problems, but also prevents self-destruction. History has taught us that is very hard to do!! Keep people who feel oppressed bottled up too long, and they can “explode.” But, the violence and self-destruction that typically manifests itself in those situations can take the focus away from the original problem.

Maybe we’ll always face this balance problem, and Christians by their presence and by their temperance can help dampen the reactions on both sides. But there is something that systemic changes cannot really fix—our hearts. We think our faith in Christ can and should make a real difference affecting healthier and long lasting cultural changes. This change comes from the inside out—from forgiven and changed hearts and minds by the gospel to changed attitudes, habits and actions.

There are a lot of implications that follow from using too much force—and especially using the force of the state to compel changes in behavior. One problem that raises its ugly head is something we can learn from history: the kinds of changes that the far left and far right want to bring about almost always demand, in the end, a totalitarian state. Is that what you want?

In modern times our world has had the French Revolution, the English Revolution, the American Revolution and the Russian Revolution…not all with the same tactics and results, but there certainly seems to be some things we can learn from these revolutions. In the most violent revolutions—the French & Russian Revolution—there was underlying unrest and when the time was right, there was an attempt to run the table on power by revolutionary power grabs, followed by dictatorships of the proletariat (or dictatorships of “fill in the blank”), followed incidentally by subsequent purity cleansing—or as they are often called: ritualistic denunciations, purges, pogroms and ethnic cleansing.

This means of change, in its most radical forms, runs the risk of a never-ending series of violent rebellion, revolution, and suppression to bring about “peace.” Is this the end game we want? Is this the end game that the Lord wants?

The passion for power—what Nietzsche called (roughly speaking) "the will to power”—with so much at stake, invites winning by any means possible. Often, that means the “slow walk” of truth finding and reforms are understandably intolerable to the oppressed, but that frustration can mean the ethics of change go out the window. Slanted propaganda, fudging the facts, and so on are marshaled by both sides. All you have to do to see this is listen to both sides of the media (in America) and compare what is focused on in reporting (and what’s left out), where and how the facts are documented and how much of the reporting depends on the narrative each side has running that provides the context for their reports. Both sides of the “divide” are prone to this human foible.

People who are oppressed or feel oppressed, often open themselves to the seduction that the desire for power brings and the temptation to go beyond gaining equality and going onto revenge. But, as we discussed above, this can easily lead to, on both small scale and large, a never ending violent series of oppression, liberation, becoming the new oppressors, being overthrown and becoming the newly oppressed and so on.

On the other hand, people in power (of all colors) fear losing their privileges, fear accountability for their abuse of power and worse, fear becoming themselves oppressed. Together, it’s a recipe for violent confrontation.

For those of goodwill among those in power, there should be a willingness to have their desires circumscribed by checks and balances, by a willingness for accountability, and by a willingness to seek and face the truth. They should be open to reasonable and Godly reforms and the sharing of power.

Summary and Closing Thoughts

Critical Theory and critical theories were not fully explored here, but enough has been considered to see that thoughtful Christians should not uncritically accept its projects and goals, nor completely reject them out of hand. The critical theories agenda should be reviewed on a case by case examination of the alleged barriers to human emancipation and the methods to change barriers, from the point of view of the gospel (critically arrived at, yet open for discussion). In some cases Christians might agree with critical theorists about what’s wrong, but differ both in how they come to that conclusion and to what extent they agree with critical theorists proposed solutions for remedy. It’s a nuanced position to take, and a problem with nuanced positions is that they have a hard time fighting the momentum that can be created by both the far right and far left.

The modus operandi of Critical Theory and critical theories is an area that Christians should be especially concerned about. It champions conflicts, enhancing cultural division, creating momentum for change and aquiring power to effect change. Part of that may be useful for highlighting social ills, but it hardly seems (especially aquiring power to effect change) something the Lord would fully endorse and something we know from history that can spillover and create as many new social evils and problems as they inially intended to solve. History should teach us that in the wings of cultural revolution reside people like Hitler, Stalin and Mao who are ready to step in and at the right time take control of it and steer it where they want it to go. Critical Theory also seems to have serious problems between its claims for objectivity (through science) and dependence on subjective testimony and anecdotal evidence.

We also wish to say Christians should be careful to allow room for reasonable disagreement among their own and others about these and many similar issues, but what they should reject—not even approach—is a full on dash to incite rapid change by means of creating increasing polarity, by fanning the flames by agitation, and thereby open the door for the kind of violent revolution that invites totalitarianism, violates human rights on all sides, and by-passes the internal changes that we believe would mark a deeper cultural movement. We also think Christians should avoid and resist pushing middle ground positions (and people) to the extreme political positions by shaming and “canceling."

We all look forward to the coming of Christ at the end of the age, but in the “mean" time, in this fallen world, with fallen people, for the glory of God, and for the common good, we should work to keep this epoch from being merely a “mean" time.

—Editor

End Notes

Endnote 1: See Rules for Radicals: A Practical Primer for Realistic Radicals. Saul Alinsky. Vintage: 1989 (originally published in 1971). See also on-line full text of the book on the Internet Archive.

Endnote 2: You can get a sense of Alinsky’s rejection of the attempt for reform through "mutual love and understanding" in this interview with members of the Rama Indian Reserve. The discussion on that mutual love and understanding as a means for social change begins at about 20:07 into the video, Alinsky begins his response to that at about 21:17.

Endnote 3: The City of God. St. Augustine of Hippo. Veritatis Splendor Publications, Reprint 2012.

Endnote 4: Christ and Culture. H. Richard Niebuhr. Harper and Row, Reprint 1975.

Endnote 5: Christ and Culture Revisted. D.A. Carson, Eerdmans, Reprint Edition (2012).

Endnote 6: See A Theory of Justice. John Rawls. Belknap Press: An Imprint of Harvard University Press; 2 edition, 1999.

Endnote 7: A great deal of the Critical Theory'a critique of Christianity (as a religion) is allegedly supported by the post-modern critique of the pretentions of objectivity…and that could include a critique of the objectivity of systematic theology. However, post-modernism (as we have said elsewhere) does not come in one flavor. It can be “…profitably categorized into two brands: metaphysical and epistemic…metaphysical (global) postmodernism is a more radical form of skepticism than epistemic postmodernism so that the former has more serious self-referential incoherence problems. That is, even if the metaphysical form were in fact true, one would have rational grounds (an undefeated defeater) for rejecting that belief. Which is to say that there is a difference between saying that we come from different perspectives seeking the truth (nothing new) and saying more radically there is no truth to the situation and only perspectives. How are we to say that the latter part of that last sentence can be meaningfully affirmed, if it undercuts itself? And, if that’s the case, as we believe it is, then it is game on for seeking the truth with humility despite our backgrounds, ethnicity, or historical contexts.

Endnote 8: In short, anecdotal evidence in some of these situations is considered worthy of trumping scholarly research. Relatively recently, some self-described academic “liberals” (and atheists) from the left decided to take on this issue (they call) “Idea Laundering” or the evidence problem: James Lindsay, Helen Pluckrose and Peter Boghossian—major players in the so-called “grievance studies affair” or as the “Sokal Squared” scandal—aimed to publish a number of purposively designed fradulent academic papers in academic journals in cultural, queer, race, gender, fat and sexuality studies to see if they could pass peer review and be accepted. They did this because they questioned the reliablity of critical studies influenced research and included in their papers “absurd facts or morally questionable acts (like chaining white men to the floor in classrooms to “help” them experience oppression). Of the 20 papers they submitted beginning in 2017—they admitted to the hoax in October of 2018—"four had been published, three had been accepted but not yet published, six had been rejected and seven were still in review.” For their “work", they received a mixed reaction within academe, some outraged by the “unethical nature of submitting deliberately bogus research”, while others praised it for exposing “flaws” believed to widespread (see this article and the section in it entitled, “Praise”). Be sure to access the link to the video panel discussion of their work included in our text (and here) and also this link to access James Lindsay’s individual analysis of it video. See also The Atlantic article, “What an Audacious Hoax Reveals About Academia."

****************

If you wish to comment or respond to this article you can do by sending them to us at:

See also our 11 minute video entitled, A Primer on Critical Theory and Its Uses.

- Jesus and Academic Culture, Part 1 (Introduction)

- Jesus and Academic Culture, Part 2 (Presenting the Gospel in Academe)

- Jesus and Academic Culture, Part 3 (Shifting From Seeking Truth to Seeking Social Justice)

- Jesus and Academic Culture, Part 5 (Answering Concerns and Critics)